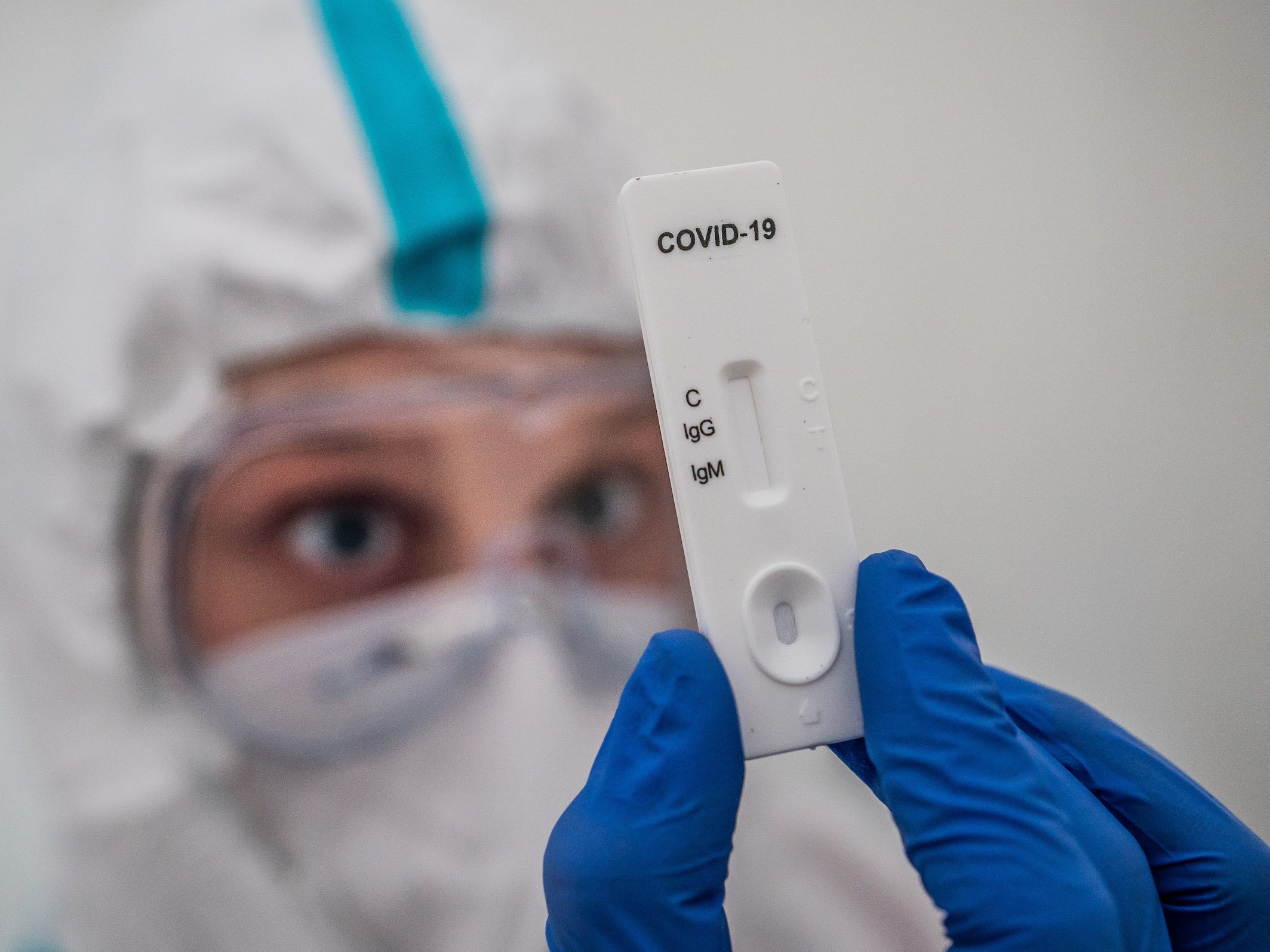

Getty

- Rapid antigen testing has become central to stopping the spread of coronavirus — but some experts have questioned their accuracy.

- Iain Buchan, a leading public health professor, spoke to Insider about the differences between rapid tests and the ‘gold-standard’ PCR tests.

- He said rapid antigen tests, also known as lateral flow tests, were a valuable tool in reducing the spread of coronavirus, especially when used frequently.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

COVID-19 rapid antigen tests, which give results in half an hour or less, have become central to the fight against coronavirus – but some experts are questioning their accuracy.

The UK government on Sunday ramped up rapid antigen testing, which tests for the current presence of the virus in your system, through a scheme that allows companies to regularly test workers even when they don’t have symptoms. The idea is to identify people who are unaware they’re infectious, so they can isolate, and stop the virus spreading.

In the US, President Donald Trump’s administration relied on rapid antigen tests, and Americans can get the test from some pharmacies and drug stores. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos said in April Amazon was working on building its own testing lab to enable the company to test its employees, including those without symptoms. President Joe Biden has said that he will ramp up testing in his COVID-19 strategy.

What is a rapid antigen test, as opposed to a PCR test?

A rapid antigen test, also called a lateral flow test, gives results in about 15 to 30 minutes. It works by detecting fragments of the virus’ genetic material. It is different to the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) tests, which are sent off to a lab to detect virus particles, and are considered the gold standard. Both tests require swabbing the nose and throat.

Experts have raised questions about the accuracy of rapid antigen testing in people with no symptoms.

A mass-testing pilot in Liverpool found Innova's lateral flow test, one of the most widely used in the UK, picked up 40% of people with no symptoms. Scientists in Birmingham tested the same device in students without symptoms, and reportedly picked up just 3% of PCR-positive cases.

In the US, Abbott's lateral flow test picked up 64.2% of people with symptoms, but 35.8% without.

John Deeks, professor of Biostatistics at the University of Birmingham, said in a statement to the Science Media Centre that rapid antigen tests should be rigorously testing for each different purpose, as if it were a new drug, before mass testing is rolled out.

Iain Buchan, clinical professor in Public Health Informatics at the University of Manchester, who was involved in the Liverpool pilot, explained to Insider the difference between rapid COVID-19 tests and the PCR tests, and why he thinks people should test themselves twice each week.

Iain Buchan

Questions and responses have been lightly edited for clarity

Dr. Catherine Schuster Bruce: What is the difference between PCR and rapid antigen testing?

Professor Iain Buchan: Lateral flows have a different role to PCR. With lateral flow, you get rapid results. The test comes to people, rather than people going to get a test.

There is sufficient biological evidence that this is a useful test of infectiousness.

PCR detects whether you have been infected.

What is the role for mass rapid antigen testing?

Public health measures very quickly need to be able to identify those who have the virus, and are infectious, so that infectious people can then quickly self isolate [for at least 10 days], and close contacts quickly self isolate too.

Does it matter what brand the test is?

The underlying technology is pretty much the same. I don't want to comment on particular makes.

Why do different studies with similar tests seem to report different conclusions?

There is no magic lab that is 100% accurate. But most of them have concluded that lateral flows pick up about one-third of infectious individuals. That's the consistent finding across all the studies. The results look different, but the numbers have actually all been very consistent.

The information is confused because the studies compare against testing PCR positive, rather than how infectious someone is.

You can't compare test results. PCR is about 40% sensitive at best, [meaning it picks up 40% of people who actually have coronavirus]. It is well known that PCR detects non-viable RNA [virus] fragments as well as viable virus, meaning that large proportions of individuals who test PCR test positive will no longer be infectious.

This means people could isolate inappropriately.

Also tests depend on background prevalence - the more people who have the virus, the more sensitive the test. PCR could still have a role to play in evaluating and understanding what is happening in the background in the community.

Do you think we have enough evidence to be rolling out antigen tests on a large scale?

There is sufficient biological evidence that this is a useful test of infectiousness.

But it's not just the biological evidence, it's behavioral and systems [evidence] that we need. It won't be one size fits all evidence here.

It's about good quality management and implementation, not just a piece of remote science.

You need to implement the tests, understand your local community and the context in which the test is being used in. And that's down to good public health practice.

How often should we be testing people?

If I was running a business and wanted to protect customers and workers, I would test them twice weekly. Tests every three days are valuable.

I think we should "test before you go" to workplaces where most mixing happens. And places like supermarkets. [Testing supermarket workers] will have a knock on effect of protecting the customer, and the local community.

Could it make people who get a negative test reckless?

We can learn that from where the tests are first applied to very large numbers of people - what are the effects on behavior of getting a negative result?

But it's not just about the negative test result. It's all the communication that goes with that. The messages from the test center, from the workplace, from your peers in the local community, from the advertising, from the local council, from government...

It's all that wrap around communication that affects what somebody does when they get the test. I think that is important. And it's changing all the time because circumstances change.

Like with any [public health] programme, it is complicated to get right. You need to pilot these things before you scale them up. And good public health practice shows that you have to keep listening to communities. You have to keep watching what happens when you deploy a public health intervention.

What would you say to someone who was worried about the false reassurance the tests could give?

I would say look at the facts, and not opinions. There is evidence coming out now that this is a really useful test. If you want to support your community then regular testing - twice per week - will really make a valuable contribution to all people around you.

But don't stop doing other things like "hands, face, space".

This will mean we can open up towns and cities earlier.

They're just another tool to make everyone safer, not a replacement for other good public health practice.