Edmond Terakopian – PA Images via Getty Images / Dr. Ali Seifi

- A neurointensivist has invented a $14 straw that may cure hiccups, nine times out of 10.

- He thinks it works by "fooling the brain," to reset the diaphragm.

- Visit Insider's homepage for more stories.

Suck on a lemon. Hold your breath. Drink water from the far side of the cup.

Home remedies for hiccups don't have a great track record. But Dr. Ali Seifi, a neurointensivist from the University of Texas at San Antonio, thinks he's invented something that can do much better. It's just a straw – that you have to suck on really hard.

"For thousands of years, human beings, and all the mammals, they have hiccups, but nobody thinks that, 'oh, this is a simple way you can stop the hiccup!'" he told Insider of his invention, which requires patients to execute a forceful, diaphragm-contracting suction – about four times harder than they would suck on a regular straw.

Hiccups are a diaphragm spasm

Seifi has seen how debilitating, hiccups can be. He's gotten them while he's teaching medicine, seen people in intensive care with head trauma suck down glass after glass of water trying to get them to go away, and watched cancer patients dealing with hiccups as a side effect of their chemotherapy treatments.

Hiccups are a chain reaction that begins when your diaphragm (the umbrella-like muscle under your rib cage that pulls air into your lungs) spasms. This is often triggered by a stimulus like spicy food, a drink, stress, or a drug.

The spasm forces the brain to send a frantic "SOS!" to the vagus nerve, which controls the epiglottis. The epiglottis is a crucial little flap at the back of your throat that organizes food into the esophagus and air into the lungs.

This alert forces the epiglottis to seal itself shut, creating the "hic" sound at the end of a hiccup.

Seifi says our evolutionary ancestors needed this one-two punch move, but we don't.

"It will take thousands and millions of years until this useless reflex goes away," he said.

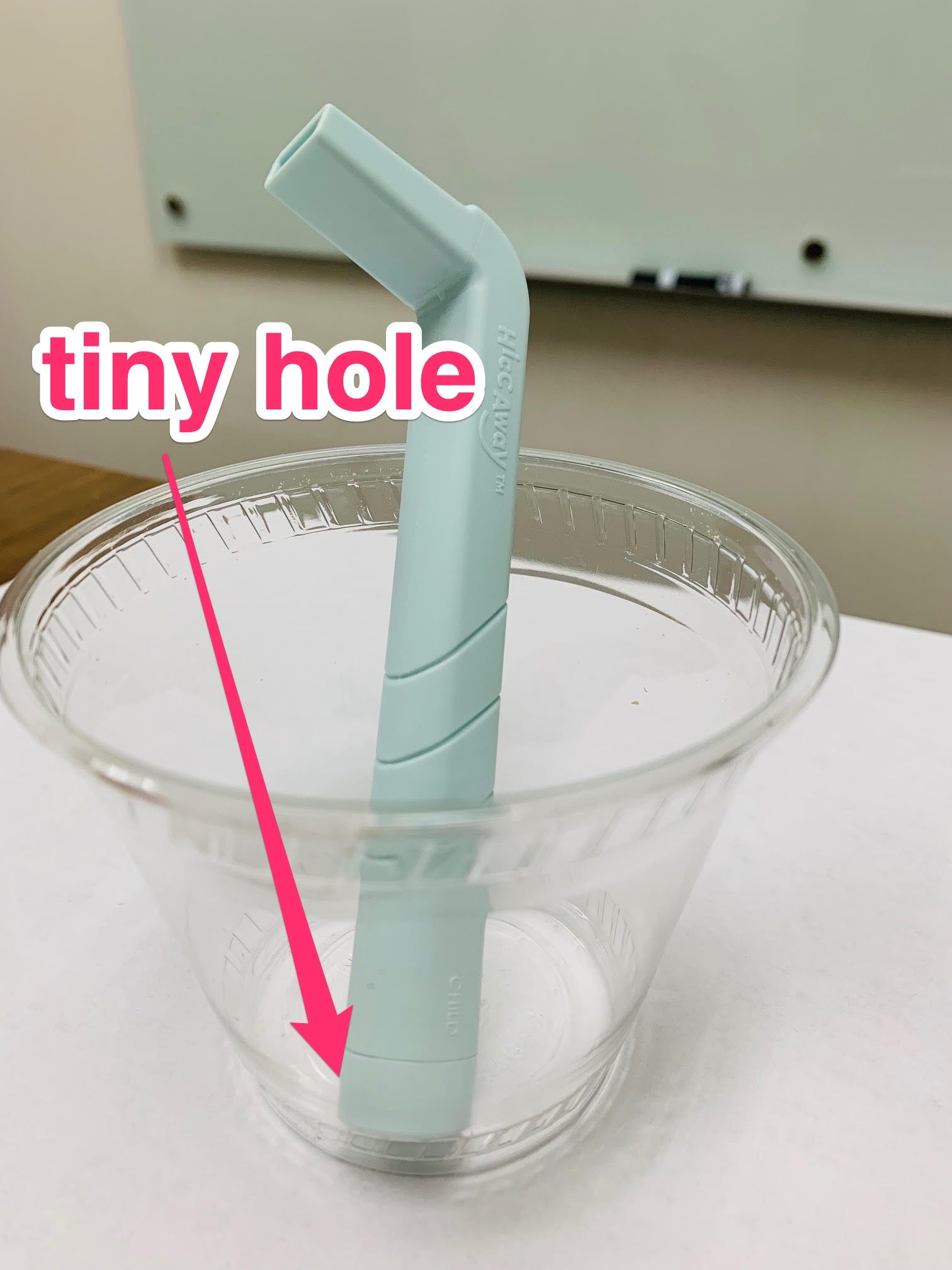

In the meantime, his new device - a $14 reusable straw called the HiccAway - is here.

According to Seifi's latest research, released in the journal JAMA Network Open on Friday, his straw cures hiccups more than nine times out of ten.

92% success rate

Courtesy of Dr. Ali Seifi

For the study, Seifi and his team deployed 290 HiccAway straws to homes around the world. Then, the researchers waited around to see who got the hiccups. Out of 249 hiccuppers who tried HiccAway, more than 90% said HiccAway worked, and that they preferred it to home remedies.

The design for HiccAway was inspired by Seifi's son's McFlurry straw (the "very, very first prototype," he called it). Now it's a patent-pending device the doctor carries around with him at all times. It's the kind of thing you could store in a cabinet next to a household thermometer, he says.

Dr. Seifi is not a hard salesman for his straw. He says you can try to make one from a McFlurry spoon by sealing up most of the small circular hole at the top, so it's a tinier opening.

To ensure that it isn't just a gimmick, Seifi is planning a gold standard randomized controlled trial with hiccup experts in Switzerland and Japan. They will test HiccAway straws against identical decoys among hundreds of hiccup-sufferers.

He believes the straw does work, and it does its job by "fooling the brain" to stop the vicious cycle between the phrenic nerve (controlling the diaphragm) and the vagus nerve (controlling the epiglottis). Users have to both contract their diaphragm (to suck) and close their epiglottis (to swallow).

"The diaphragm keeps being occupied by our intention of suctioning the water. Then, the brain forgets to keep spasming that diaphragm."