Roxiller/Getty Images

- The world of cheese is vast, with a near-endless amount of varieties and styles.

- From fresh Chevre to aged Grana Padano, each cheese has its own personality due to how it's made.

- Knowing what's out there can help you discover new cheeses and hone your personal taste.

- Visit Insider's Home & Kitchen Reference library for more stories.

Most Americans don't grow up eating fancy cheese. The cheese you snacked on as a kid may have been orange and shredded. Brie was probably a later discovery, and you may still be unsure whether you can or should eat the rind.

But if you simply love cheese, you have more in common with cheese experts than you think, even if you can't tell a Parmigiano from a Pecorino.

If you're ready to expand your horizons, below are the most common categories cheesemongers use and which cheese families fall under these categories. Knowing these styles will help you shop for cheese more efficiently, help you understand your preferences, and give you confidence in conversations with even the stuffiest cheesemonger.

Cheeses are most simply categorized as soft, semi-soft, or hard. But industry pros often break these categories down further, grouping them more according to how they're made.

How cheese is made

Atlantide Phototravel/Getty Images

Before we get into the various families, it's useful to talk a bit about how cheese is made. Cheese is a beautiful, historic product with an immense amount of cultural and anthropological value. It's also kind of just milk jerky - dehydrated milk fat and protein.

The process of making cheese harnesses the spoilage process, like when old milk in your fridge becomes chunky, but in a way that's tasty, practical, and safe. Because this relies on natural processes, cheese folk like to say that cheese was discovered, not invented.

Milk is 80 to 90% water. The rest is fat, protein, minerals, and sugar (known as lactose). The primary ingredient in cheese is milk, plus three other important ones: cultures, rennet, and salt. The addition of each of these ingredients kickstarts a different step in the cheesemaking process:

- Culture: The cheese-making process begins when a culture called lactobacillus, known as lactic acid bacteria, is added to milk. It ferments lactose into lactic acid (this is why most cheese is very low in lactose or even lactose-free).

- Rennet: An enzyme called rennet separates the solid curds from the liquid whey, a process called coagulation.

- Salt: After the whey is drained off, salt is added. Salt is important for flavor, of course, but it also helps regulate the bacterial changes that continue until the cheese makes its way to your plate.

From here, the curd is manipulated in one way or another to make the cheeses we know and love. If it's meant to become a hard, dry cheese like Parmigiano Reggiano, the curds are cut into teeny tiny pieces the size of a grain of rice to remove the liquid. For a Brie-style cheese, the curd is kept in large pieces, and gently scooped or even hand-ladled into large molds, so the curd maintains its moisture.

Most cheeses spend at least a little bit of time ripening or "aging." Cheese pros prefer the term "ripening" because most cheese doesn't age very long; it's rare that it'll be aged for longer than two years.

As a cheese ripens, the cultures added at the beginning of the process work on the fat and protein in different ways to give the cheese its personality. The end result, depending on how it's processed and ripened, will fall into one of the following categories:

Soft cheeses

The hallmark of this category is its high moisture content - generally 50 to 60%. Even though soft cheeses can feel decadent, that's generally due to their water content and not to exorbitant amounts of fat. These cheeses may be squishy, creamy, oozy, fluffy, spreadable - or a combination of these.

Cheesemongers break "soft cheeses" into:

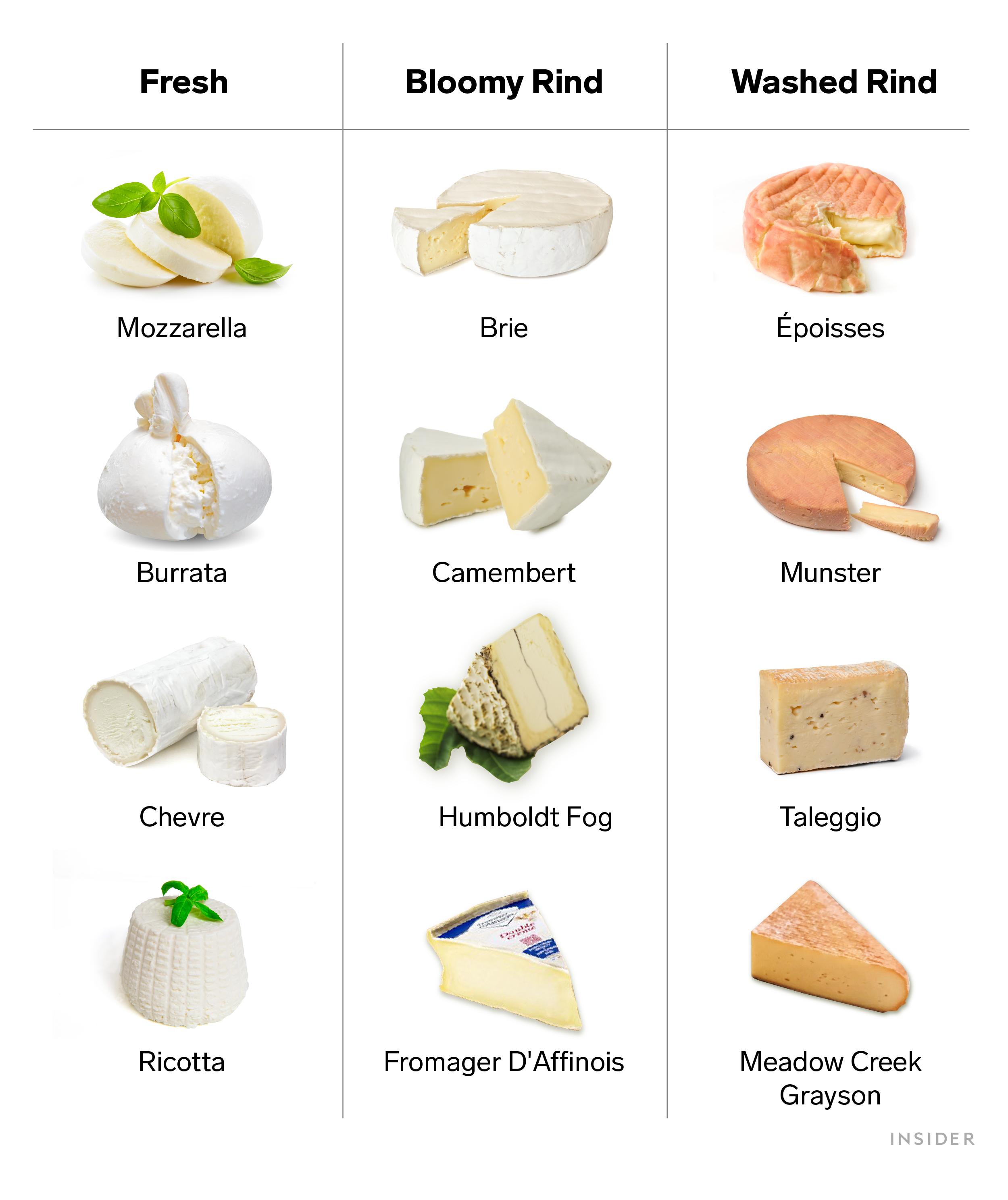

Fresh cheese

svariophoto/Getty Images

These are the youngest cheeses you can find. They generally don't spend any time ripening, meaning they're the closest in flavor to milk.

Bloomy rind cheese

stoica ionela/Shutterstock

Cheeses made in this style have a culture added called penicillium candidum or penicillium camemberti. The baby cheese, which looks like a little wheel of queso fresco, starts to sprout what looks like dandelion fuzz on the outside. Because it looks like the fuzz is blooming, cheese folks call this style "bloomy rind."

The cheese ager or "affineur" pats that fuzz down into what becomes the cheese's rind. The rind is what breaks down the fat and protein of the curd into the pudgy texture and mushroomy flavors that we associate with this style of cheese.

You may see these cheeses labeled as "double cream" or "triple cream." That means that cream has been added to the whole milk. Triple creams have more cream added than double creams.

Washed rind cheese

Picture Partners/Shutterstock

Washed rind cheeses are the "stinky cheeses" of the cheese world. Most start their lives as bloomy rinds, then during the ripening process, are gently scrubbed down with brine, a culture solution, or sometimes diluted wine or beer.

This invites a host of funky, meaty bacteria that makes the cheese smell like feet but taste like bacon custard. Depending on their ripeness, cheese pros classify some of these as soft and some as semi-soft. This style was created/discovered by monks in the middle ages.

Semi-soft cheeses

The easiest way to think about a semi-soft cheese is in relation to soft cheeses and hard cheeses. When you break most soft cheeses, they'll either ooze or crumble into wet lumps. When you break most hard cheeses, they'll give you some resistance.

When you break a semi-soft cheese, it breaks much more easily, but you don't have to worry that it will ooze on you. Just a clean, simple break. These cheeses generally have a moisture content of 45 to 50%.

Cheesemongers break "semi-soft cheeses" into:

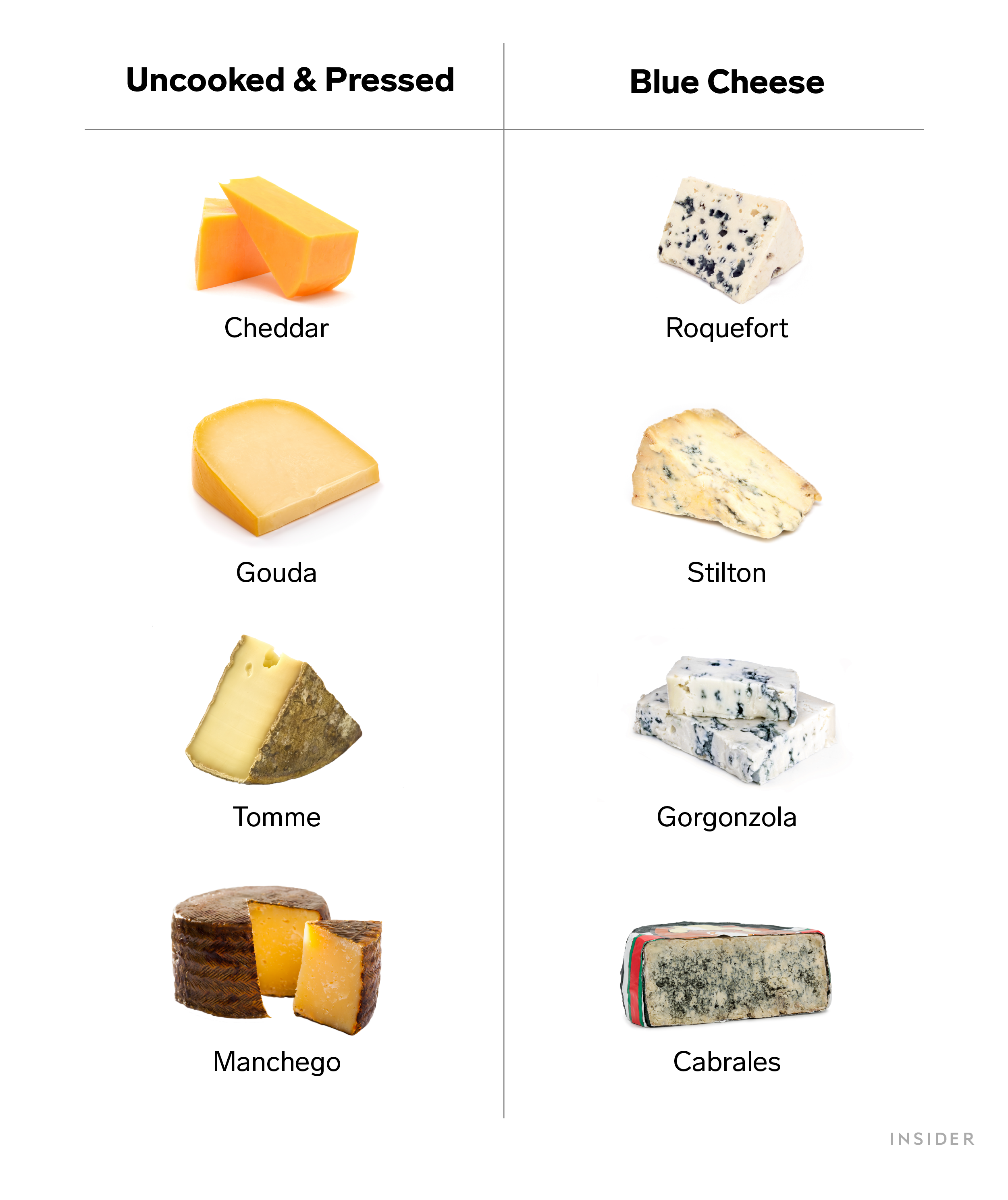

Uncooked and pressed

After the curds are separated from the whey, curds are milled down and pressed directly into a form.

Blue cheese

grafvision/Shutterstock

Cultures called penicillium roqueforti or penicillium glaucum are responsible for the blue mold in blue cheese. After the wheels are formed, they're pierced with stainless steel needles, so oxygen can activate the blue mold.

Having trained many new cheesemongers, I can tell you that most people don't like blue cheese when they're new to cheese. If you keep tasting it, though, especially with a sweet pairing like honey or caramel, you may find that it grows on you.

Hard cheeses

Hard cheeses generally have a 35 to 45% moisture content. Because the aging process generally leads to moisture evaporation, cheeses aged for a year or more are probably considered hard cheeses, even if they're not in the list below. Some aged cheddars, goudas, and manchegos qualify as hard cheeses.

Cheesemongers break "hard cheeses" into:

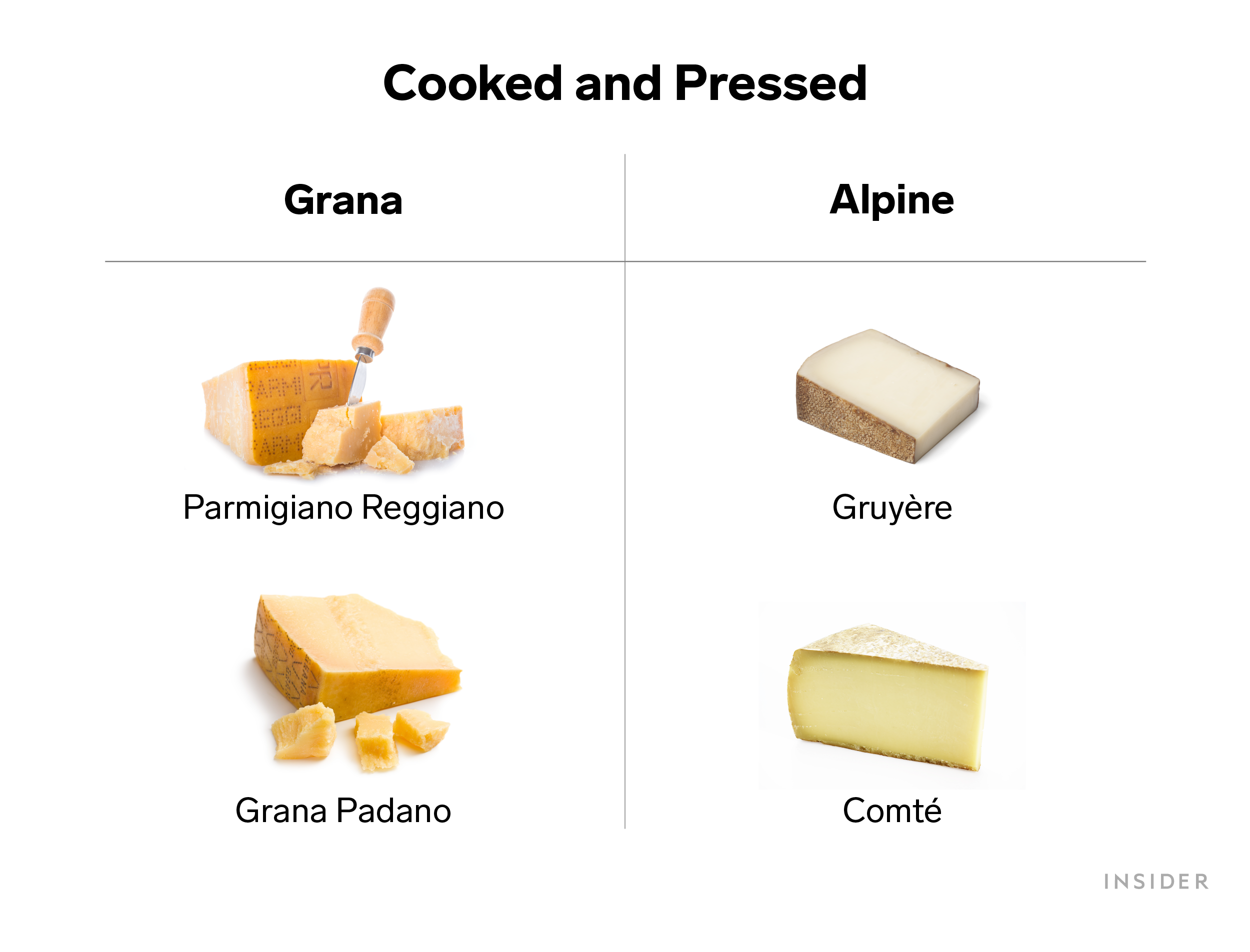

Cooked and pressed

Mauro69/Getty Images

Curds are heated before pressing, which knits the curds tightly together. This style is generally broken into two styles: Grana (like Parmigiano) and Alpine (like Gruyere).

Insider's takeaway

If you're a little dizzy, I don't blame you! The world of cheese is vast and broad and there's always more to learn. If you want to continue learning about cheese, the most important thing is to keep tasting it. Go to cheese shops where there are patient, knowledgeable mongers who can help you find your new favorite cheese. Above all, have fun!