- By July 1940, shortly after France had surrendered to Germany, the British outlook was bleak.

- The British were especially worried that Axis navies would seize and use France's warships.

- To prevent that, the British launched an operation to take France's fleet out of the equation.

Early on July 3, 1940, a massive British Royal Navy task force assembled off of Mers-el-Kébir in what was then French Algeria. The port was home to a small but powerful French Navy squadron that had fought alongside the British against Germany and Italy weeks earlier.

This time, however, the Royal Navy was not arriving as an ally. Following France's surrender to the Germans two weeks before, the British worried that France's warships would soon be seized and pressed into service by the Axis.

Determined to prevent that, the British sent the Royal Navy to deliver an ultimatum to the French. What followed was the largest single naval action of the war up to that point — and a victory no one was proud of.

A desperate situation

Britain's outlook was bleak in July 1940. The French government had surrendered to Germany on June 25 and was transferring power to the collaborationist Vichy regime led by Marshal Philippe Pétain. With the continent firmly under Axis control, the British were isolated and seriously concerned about a German invasion.

The Royal Navy — Britain's first line of defense against an invasion — was chiefly concerned that if the Axis acquired France's fleet, then the fourth-largest in the world, the naval balance of power could shift in the Axis' favor, especially in the Mediterranean, where Italy's fleet was already considered a large threat.

France's armistice with Germany stated that neither Germany or Italy would confiscate the warships, but it also required all of France's warships to "collect in ports ... under German and/or Italian control to demobilize," and the British had no reason to trust Hitler that would abide by the terms.

At the time, most of France's warships were in British or British-controlled ports or in the ports of France's own overseas possessions. Consequently, the British made two plans: Operation Grasp would seize all French ships in Britain, while Operation Catapult involved seizing all French ships in the Mediterranean, mainly at Alexandria and Mers-el-Kébir.

The French would be given an ultimatum: Sail the ships out and continue fighting alongside the British; turn the ships over to the British, who would return them or compensate France for them after the war; or sail them to French territory in the Caribbean to demilitarize them or turn them over to the US until the end of the war.

If the French refused those options, they would need to scuttle their ships within six hours. If they refused that, then the British would "use whatever force may be necessary" to prevent the ships from falling into Axis hands.

Battle at Mers-el-Kébir

The French force at Mers-el-Kébir, commanded by Adm. Marcel Gensoul, consisted of four battleships, including the flagship Dunkerque, six destroyers, and a seaplane tender.

The Royal Navy force sent from Gibraltar to deliver the ultimatum, called Force H, arrived off Mers-el-Kébir around 5:30 a.m. on July 3. Led by Rear Adm. Sir James Somerville, it consisted of the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, a battlecruiser, two battleships, two light cruisers, and 11 destroyers.

Somerville didn't speak French, so he sent Ark Royal's captain, Cedric Holland, to deliver the ultimatum to Gensoul. Holland was fluent in French and had been a naval attaché in Paris. Somerville, desperate to avoid violence, hoped this would help negotiations go smoothly. It had the opposite effect.

Gensoul was insulted that the British had only sent a mere captain to speak with him and refused to meet. Instead, Holland met Gensoul's flag lieutenant, Bernard Dufay, on a boat at the mouth of the harbor at 8:10 a.m. The difficult negotiations were made more cumbersome by the time Dufay needed to travel between ships and confer with Gensoul.

Dufay relayed the written ultimatum to Gensoul, who repeatedly rejected it and said that opening fire "will result in immediately ranging the whole French Feet against Great Britain."

Gensoul also informed his superiors that the British had demanded he sink his ships within six hours or be fired on, omitting the other options. They ordered him to stand firm, and French crews began to prepare their ships.

Somerville set a 3:00 p.m. deadline. To show their seriousness, British aircraft dropped magnetic mines at the mouth of the harbor. When Gensoul finally agreed to meet Holland aboard Dunkerque, the deadline was extended to 5:30.

The French officer told his British counterpart that his superiors had ordered the ships be scuttled if the Germans or Italians tried to seize them, but the British weren't willing to risk their capture, and no agreement was made. With no agreement and reports that other French ships on their way, Holland left the Dunkerque at 5:25 p.m.

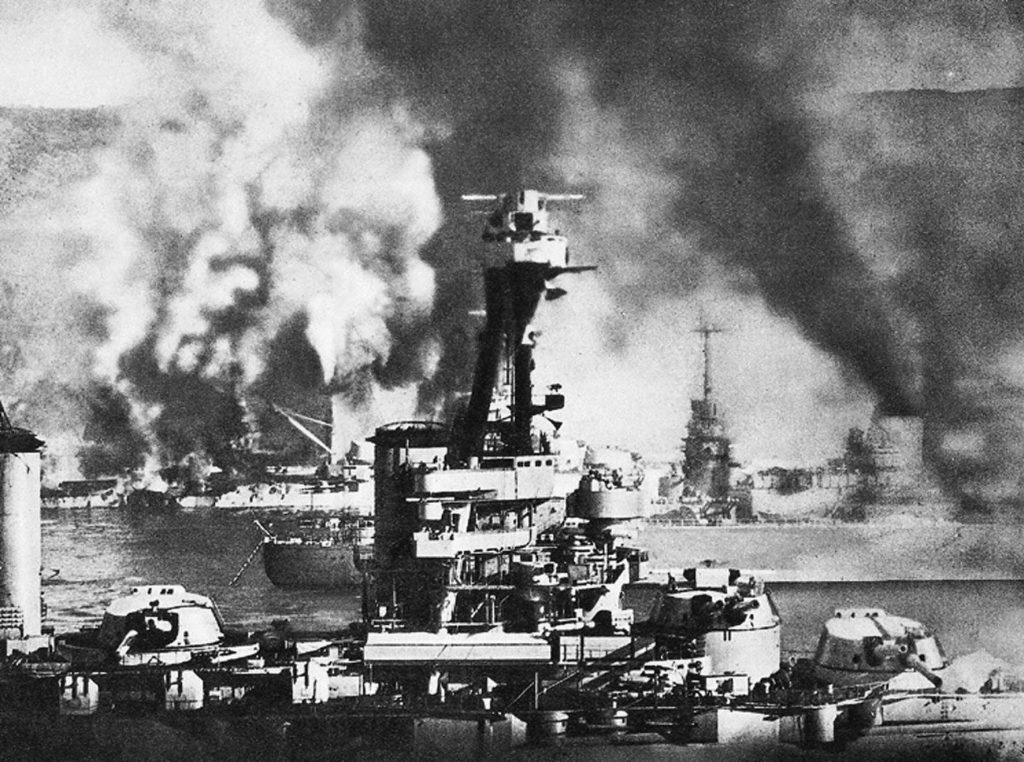

At 5:54, the British opened fire. Still docked in tight lines, the French squadron stood no chance. As the first shells fell, Gensoul ordered his ships to return fire and attempt to escape.

Dunkerque was hit four times as it pulled away, killing hundreds and immediately disabling the ship. Its crew beached the battleship to keep it from sinking. The battleship Bretagne was hit four times, detonating one of its magazines and ripping a huge hole in the hull. Within minutes, it capsized and sank with 977 of its crew.

Around the same time, the destroyer Mogador was hit, blowing apart its stern and immobilizing it immediately. Multiple hits then set the battleship Provence ablaze and it settled to the bottom of the harbor.

After 10 minutes, Somerville ordered a cease fire to allow the French to abandon their ships, which were almost all damaged. Gensoul, possibly trying to buy time, signaled that he would now accept the Royal Navy's terms. Somerville's reply was blunt: "unless I see your ships sinking, I shall open fire again."

Only the battleship Strasbourg and two destroyers escaped. The rest of the squadron was wrecked. The raid left 1,297 French sailors dead, while only two British aviators were killed when their aircraft was shot down.

'Unnatural and painful'

The British had approached the mission with dismay. Somerville and Holland both vigorously protested the use of force against the French.

Before leaving Gibraltar, Somerville received a message from Churchill acknowledging that his task was "one of the most disagreeable and difficult tasks that a British Admiral has ever been faced with" but expressing "complete confidence" that he would "carry it out relentlessly."

While President Franklin Roosevelt saw it as proof of British resolve, the British saw little to celebrate. Churchill himself later called it "a hateful decision, the most unnatural and painful in which I have ever been concerned." The Vichy regime broke off relations afterward and used the clash to stoke anti-British sentiment.

The British also seized French ships in Alexandria and Britain on July 3. The ships in Alexandria were taken without incident but four sailors were killed during the seizure of a French submarine at Plymouth.

Ultimately, the French made good on Gensoul's assurances that they would keep their ships out of Axis hands. When the Germans tried to seize the French fleet at Toulon in November 1942, the French scuttled almost every ship.