- In the last few years, we’ve seen record-breaking temperatures, intense hurricanes and wildfires, and unprecedented ice melt.

- All of these are predicted consequences of climate change and are expected to get worse in the coming years.

- Addressing this threat in the next 10 years is critical: Scientists say the world must slash its carbon emissions in half by 2030 to avoid catastrophic warming.

- Here’s what we can expect in the next decade.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more.

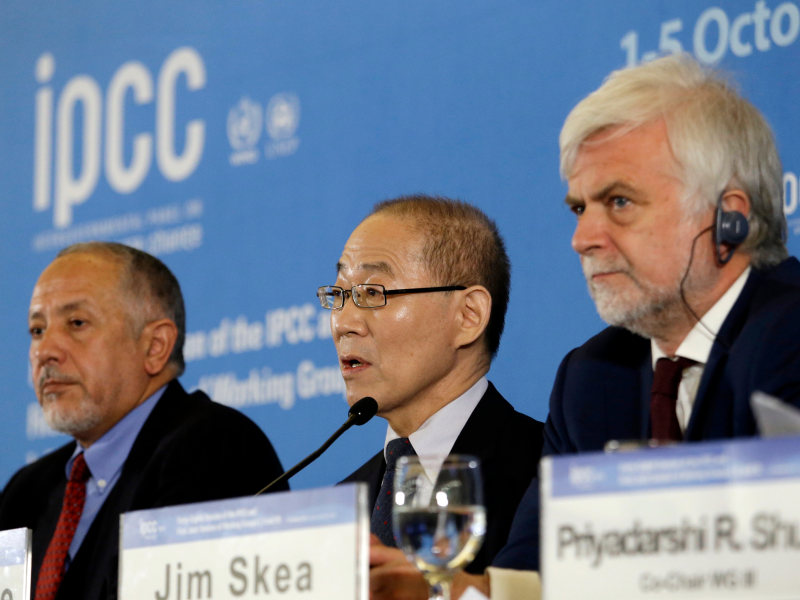

We only have a decade to avoid the worst consequences of climate change.

That’s the warning the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) put out last year. But so far, nations are not slashing emissions enough to keep Earth’s temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels – the threshold established in the Paris climate agreement.

“What we know is that unabated climate change will really transform our world into something that is unrecognizable,” Kelly Levin, a senior associate at the World Resources Institute’s climate program, told Business Insider.

That transformation has already begun. The last few years saw record-breaking temperatures, catastrophic and bizarre storms, and unprecedented ice melt. That’s all likely to get worse by 2030.

Here's what we can expect in the next 10 years.

Scientists attribute the increasing frequency of record-breaking temperatures, unprecedented ice melt, and extreme weather shifts to greenhouse-gas emissions.

Fossil fuels like coal contain compounds like carbon dioxide and methane, which trap heat from the sun. Extracting and burning these fuels for energy releases those gases into the atmosphere, where they accumulate and heat up the Earth over time.

"As long as we burn fossil fuels and load the atmosphere with carbon pollution, it all gets worse," climate scientist Michael Mann told Business Insider in an email.

Last year, the IPCC warned that we only have until 2030 to act in order to avoid the worst consequences of severe climate change.

According to the IPCC, the world's carbon emissions have to fall by 45% by 2030 to keep the world's average temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

So the next 10 years are crucial for any efforts to slow this trend.

If Earth warms more than 1.5 degrees, scientists think the world's ecosystems could start to collapse.

"The choices that we make today are going to have profound impacts," Levin said.

Even if nations stick to the goals they set under the Paris climate agreement, emissions will still likely be too high, according to the IPCC.

Under the voluntary goals set in the Paris agreement, the world would still emit the equivalent of 52 to 58 gigatons of carbon dioxide per year by 2030, according to the report. (This is measured as an "equivalent" in order to factor in other greenhouse gases, like methane, which is 84 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide.)

So far, most countries are not on track anyway.

Regardless of what actions we take, there are a few changes scientists know we'll see in the next 10 years.

That's because the world will keep getting warmer even if we stop emitting greenhouse gases immediately.

In the worst case scenario, we might even the 1.5-degree temperature-rise mark by 2030.

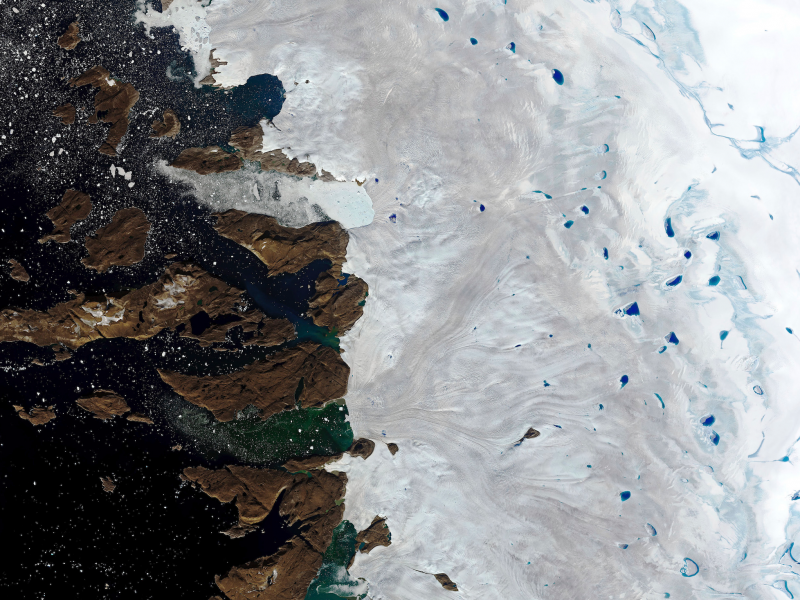

The globe's ice caps will continue to melt, and crucial ice sheets like the one in Greenland might start down an irreversible path toward disappearing completely.

"Somewhere between 1.5 and 2 degrees, there's a tipping point after which it will no longer be possible to maintain the Greenland Ice Sheet," Ruth Mottram, a climate scientist at the Danish Meteorological Institute, told Inside Climate News. "What we don't have a handle on is how quickly the Greenland Ice Sheet will be lost."

Greenland's ice is already approaching that tipping point, according to a study published in May. Whereas the melting that happened during warm cycles used to get balanced out when new ice formed during cool cycles, warm periods now cause significant meltdown and cool periods simply pause it.

That makes it difficult for the ice sheet to regenerate what it's losing.

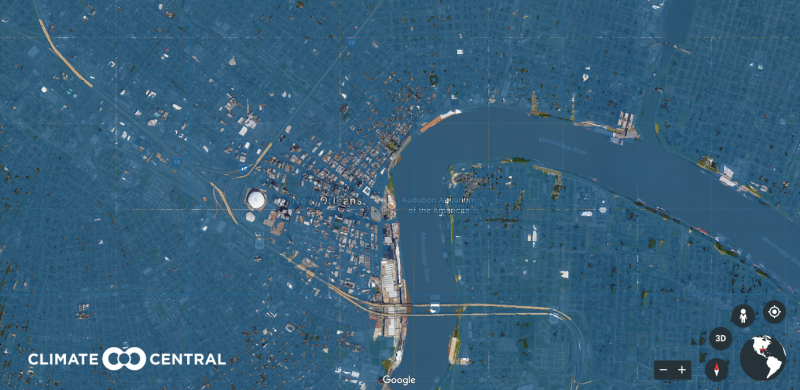

That will lead to more sea-level rise — about 0.3 to 0.6 feet on average globally by 2030, according to the US' National Climate Assessment.

In addition to melting ice, rising ocean temperatures cause seas to rise because warm water takes up more volume. As the globe heats up, scientists expect that simple fact of physics to account for about 75% of future sea-level rise.

The risk of high-tide flooding (which happens in the absence of storms or severe weather) is rapidly increasing for communities on the US Gulf and East Coasts.

In 2018, the US Northeast saw a median of one major sunny-day flood per year. By 2030, projections suggest the region will see a median of five such floods per year. By 2045, that number could grow to 25 floods.

The rising seawater won't be distributed evenly across the globe.

Low-lying countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam, and the Seychelles are especially vulnerable. Rising oceans have already begun to threaten cities like Miami, New Orleans, Venice, Jakarta, and Lagos.

Some areas could see sea levels up to 6 feet higher by the end of the century.

Extra warmth and water means hurricanes will become slower and stronger. In the next decade, we're likely to see more cyclones like Hurricane Dorian, which sat over the Bahamas for nearly 24 hours.

That's because hurricanes use warm water as fuel, so as Earth's oceans and air heat up, tropical storms get stronger, wetter, and slower.

Over the past 70 years or so, the speed of hurricanes and tropical storms has slowed about 10% on average, according to a 2018 study.

When storms are slower, their forceful winds, heavy rain, and surging tides have much more time to cause destruction. In the Bahamas, Dorian leveled entire towns.

"The slower you go, that means more rain. That means more time that you're going to have those winds. That's a long period of time to have hurricane-force winds," National Hurricane Center director Ken Graham said in a Facebook Live video as Dorian approached the Bahamas.

A study published earlier this month found that the frequency of the most damaging hurricanes has increased 330% century-over-century.

To make matters worse, a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture. The peak rain rates of storms have increased by 30% over the past 60 years.

That means up to 4 inches of water per hour. Hurricane Harvey in 2017 was a prime example of this: After it made landfall, Harvey weakened to a tropical storm then stalled for days, dumping unprecedented amounts of rain on the Houston area. Scientist Tom Di Liberto described it as the "storm that refused to leave."

Hurricanes are likely to intensify more rapidly as well.

"It's pretty well understood that if the water is warmer and it's causing more moist air to come up, you have the potential of a storm to grow quickly and intensely," Brian Haus, a researcher who simulates hurricanes at the University of Miami, previously told Business Insider.

Overall, extreme weather is expected grow more common and intense.

"Certain types of extreme events in the US have already become more frequent and intense and long-lasting," Levin said. "There's no reason to think that we're not going to start to see an amplification of what we've been seeing."

The World Health Organization (WHO) projects that, overall, climate change will kill an additional 241,000 people per year by 2030.

The WHO expects that heat-related illnesses will be a major culprit, killing up to 121,464 additional people by 2030.

In the coming years, experts expect to see "day zeros" — the term for the moment when a city's taps run dry.

In January 2018, Cape Town, South Africa, got dangerously close to this reality: The government announced the city was three months from day zero. Residents successfully limited their water use enough to make it to the next rainy season, however.

The IPCC projects severe reductions in water resources for 8% of the global population from 2021 to 2040.

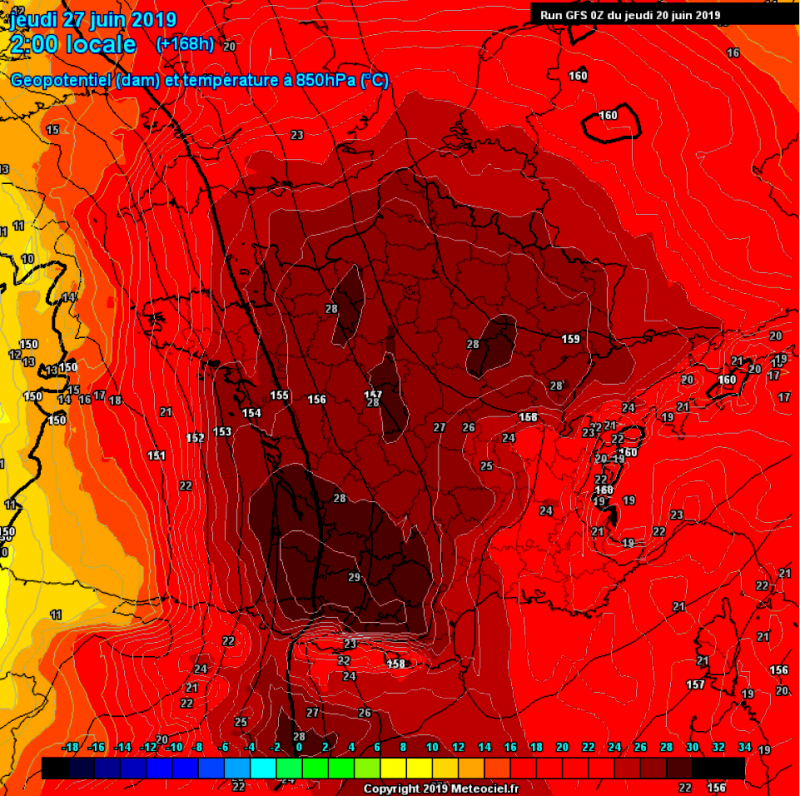

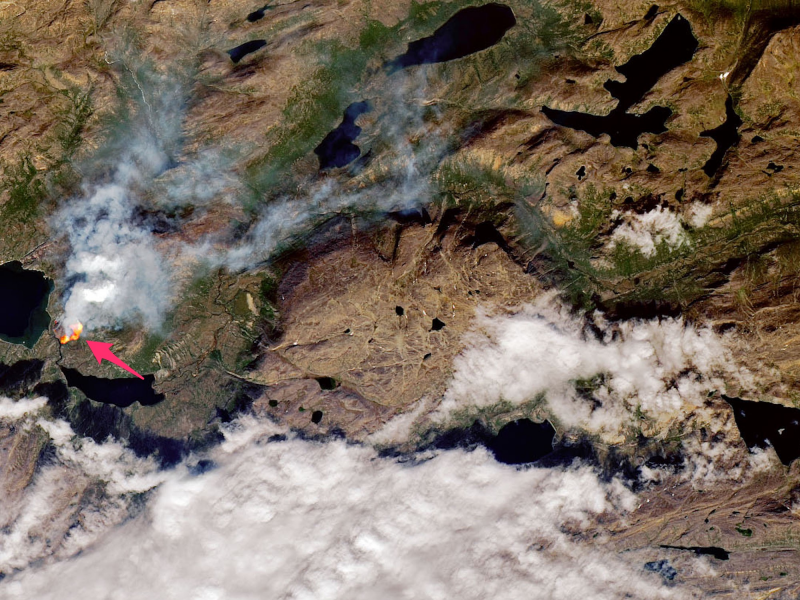

Dry vegetation in hot regions lights up easily, which means more frequent, bigger wildfires.

"Climate change, with rising temperatures and shifts in precipitation patterns, is amplifying the risk of wildfires and prolonging the season," the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) said in a July release.

A 2016 study found that climate change nearly doubled the amount of forest that burned in the western US between 1984 and 2015, adding over 10 billion additional acres of burned area. In California in particular, the annual area burned in summer wildfires increased fivefold from 1972 to 2018.

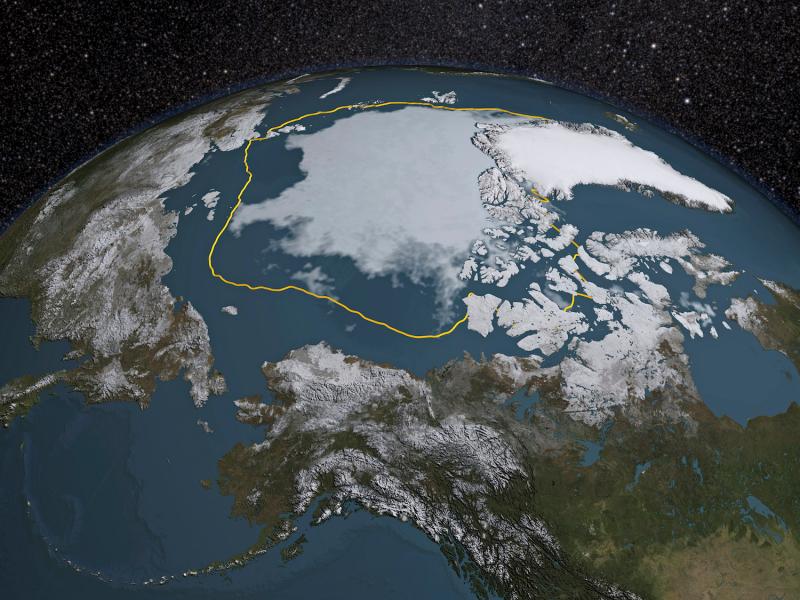

We're also likely to see more wildfires in the Arctic, which is warming almost twice as fast as the global average. That means Arctic sea ice is also disappearing.

Rapid warming means that crucial sea ice is melting, which accelerates warming even more.

"You take what was a reflective surface, the white ice, and you expose darker oceans underneath it," Levin said. "That can lead to a much greater absorption of solar radiation, and knock-on warming impacts as well as change of weather patterns."

The Amazon rainforest is in trouble as well, largely because farmers and loggers are cutting it down so rapidly.

A 2008 study projected that humans would clear away 31% of the Amazon by 2030. Another 24% would be damaged by drought or logging, the study found.

People have already cut down 20% of the Amazon. If another 20% disappears, that could trigger a feedback loop known as a "dieback," in which the forest could dry out and become a savannah.

"The risk of transforming the Amazon to a savannah-like state — it could have a tremendous impact for our ability worldwide to get a handle on the climate-change problem," Levin said.

That's because the Amazon stores up to 140 billion tons of carbon dioxide - the equivalent of 14 decades' worth of human emissions. Releasing that would accelerate global warming.

"You have a vital carbon sink no longer acting as a carbon sink, but instead acting as a carbon source," Levin added.

Other crucial ecosystems face collapse in the next decade as well. At present rates, it's expected that 60% of all coral reefs will be highly or critically threatened by 2030.

High ocean temperatures can cause coral to expel the algae living in its tissue and turn white, a process called coral bleaching.

It's an increasingly dire problem, given that oceans absorb 93% of the extra heat that greenhouse gases trap in the atmosphere. Recent research revealed that the seas are heating up 40% faster, on average, than the prior estimate.

The consequences of coral bleaching extend beyond the coral itself, since reefs house 25% of all marine life and provide the equivalent of $375 billion in goods and services each year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

About 55% of the world's oceans could suffer due to rising temperatures, acidification, decreasing oxygen, and other symptoms of climate change by 2030.

These largely irreversible changes will eventually force mass migrations of marine life, upend ocean ecosystems, and threaten human livelihoods that depend on the ocean, according to a 2017 study. Many species that can't adapt could die out.

"Climate impacts are also going to exacerbate social inequality," Levin said.

That's because people with fewer resources will be less able to avoid the worst impacts.

"That National Climate Assessment shows that residents, for example, in rural communities who often have less capacity to adapt, are going to be especially hard-hit given their dependence on agriculture," Levin explained.

She added: "You can think also of the scenario of the poor who live in cities who could be at greater exposure to heat stress if they lack air conditioning and heat waves increase in frequency and duration."

A 2015 report from the World Bank predicted that the climate crisis will push an additional 100 million people into extreme poverty by 2030.

That's because global crop yields could fall by 5% by 2030 in the face of climate change, according to the report. That will make food more scarce and more expensive, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.

Ultimately, "nobody is free from the impacts of climate change," Mann said.

"If you're on the coast, you're treated by hurricanes and sea-level rise," he added. "If you're in the western US, more intense, faster-spreading wildfires, worse drought. And we're seeing unprecedented heat waves and flooding events throughout the US."

To avoid these devastating consequences, "we need annual emissions to be about half of what they are now by 2030," Levin said.

That means "we need to shift across the board in terms of policies, technologies, and behavior," she added.

Scientists say the world has to shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy, especially transforming the way we travel and produce food.

"That means we need politicians who are willing to act in our interest rather than on the part of vested interests," Mann said. "Voting in the 2020 election is probably the single-most important thing we can do to address climate change."

Levin and the IPCC both say that, since we're so far off the path towards quitting fossil fuels, the transition will also require technologies that suck carbon out of the atmosphere.

"It's definitely going to be a massive undertaking, but the risks are so large that we can't afford not to do it," Levin said.